This is Chapter 6 in a series. If you’re new to the series, visit the series home page for the full table of contents.

_________

Chapter 6: The American Brain

In Chapter 5 we became acquainted with some new toys: the Idea Spectrum, the Thought Pile, and the Speech Curve. Now it’s time to play with them.

We finished the chapter with a paragraph full of questions:

How do millions of citizens, holding a wide range of views, often in furious conflict with each other, actually function as a single brain in practice? How does the brain form opinions? How does it learn new things? How does it make concrete decisions, and how does it change its mind?

The big U.S. brain thinks using the same system it employs to distribute resources and elect leaders: the Value Games. The First Amendment, in addition to providing a key liberty, opens up a whole new competitive playing field:

The Marketplace of Ideas

It’s well known that the economic marketplace is all about supply and demand—a supply of products and services satisfies the demand for all kinds of things, like homes, cars, food, and healthcare. The two components react to and influence one another. Demand drives supply as supply scrambles to match it, and suppliers try to manipulate demand to drive it towards whatever they’re supplying.

We don’t always think of it like this, but the marketplace of ideas (MPI) works the same way. The demand for everything from knowledge to wisdom to leadership to entertainment to emotional catharsis is met by an endless supply of human expression. But there isn’t really an established way to analyze the MPI the way there is with economics, so we’ll come up with our own way of doing it, using the new language we’re developing.

In its most basic form, the MPI is an attention market, where attention is the key currency instead of money.

Economic demand is generated by consumer preferences; demand in the MPI is a function of listener preferences. The listener is the consumer of expressed ideas—and in the same way economic consumers have limited money to spend, idea consumers have limited time to spend listening.

Economic supply is made up of products and services, and economic suppliers are sellers; supply in the MPI is ideas, supplied by speakers (“speakers,” in this case, means anyone exerting any form of expression—speech, writing, art, etc.).

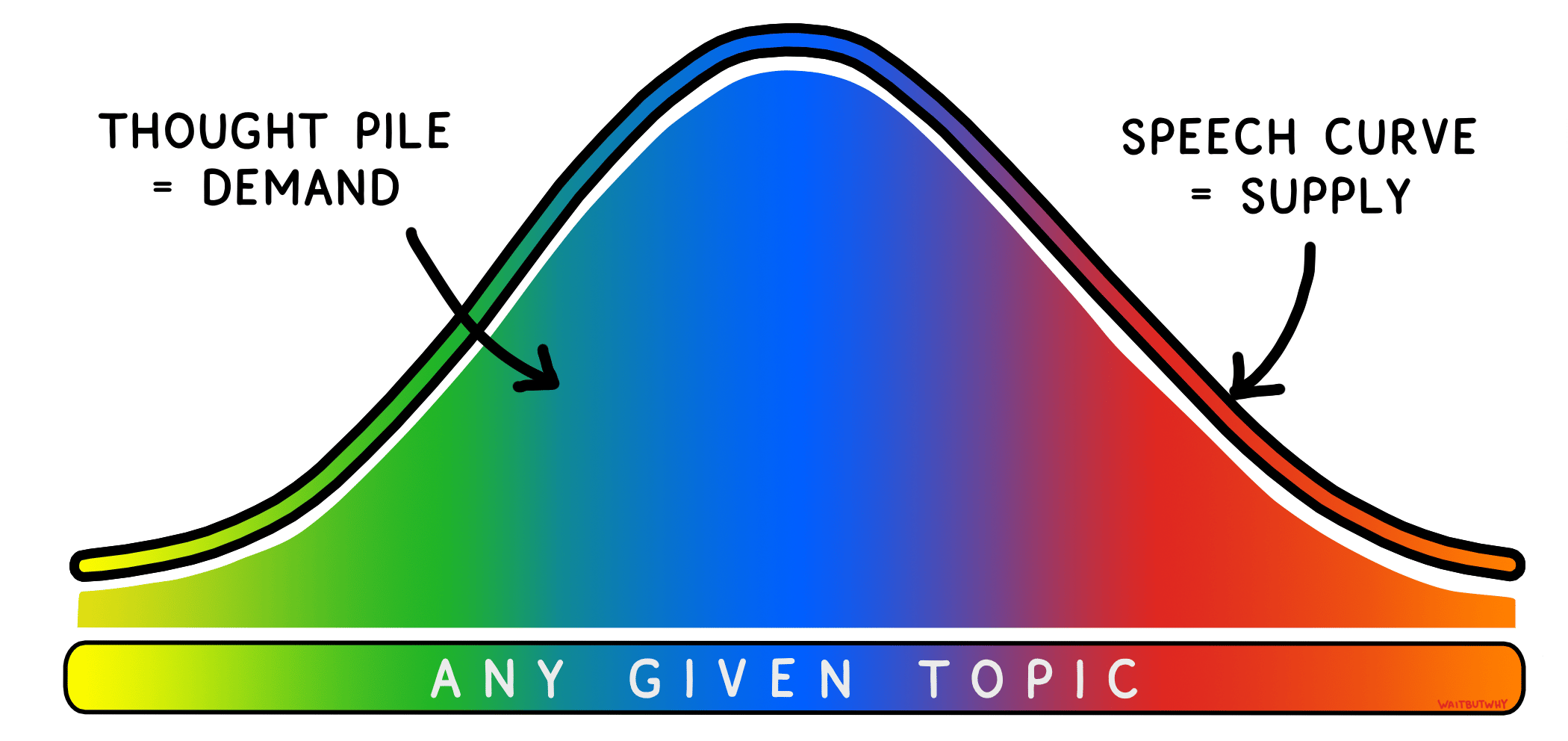

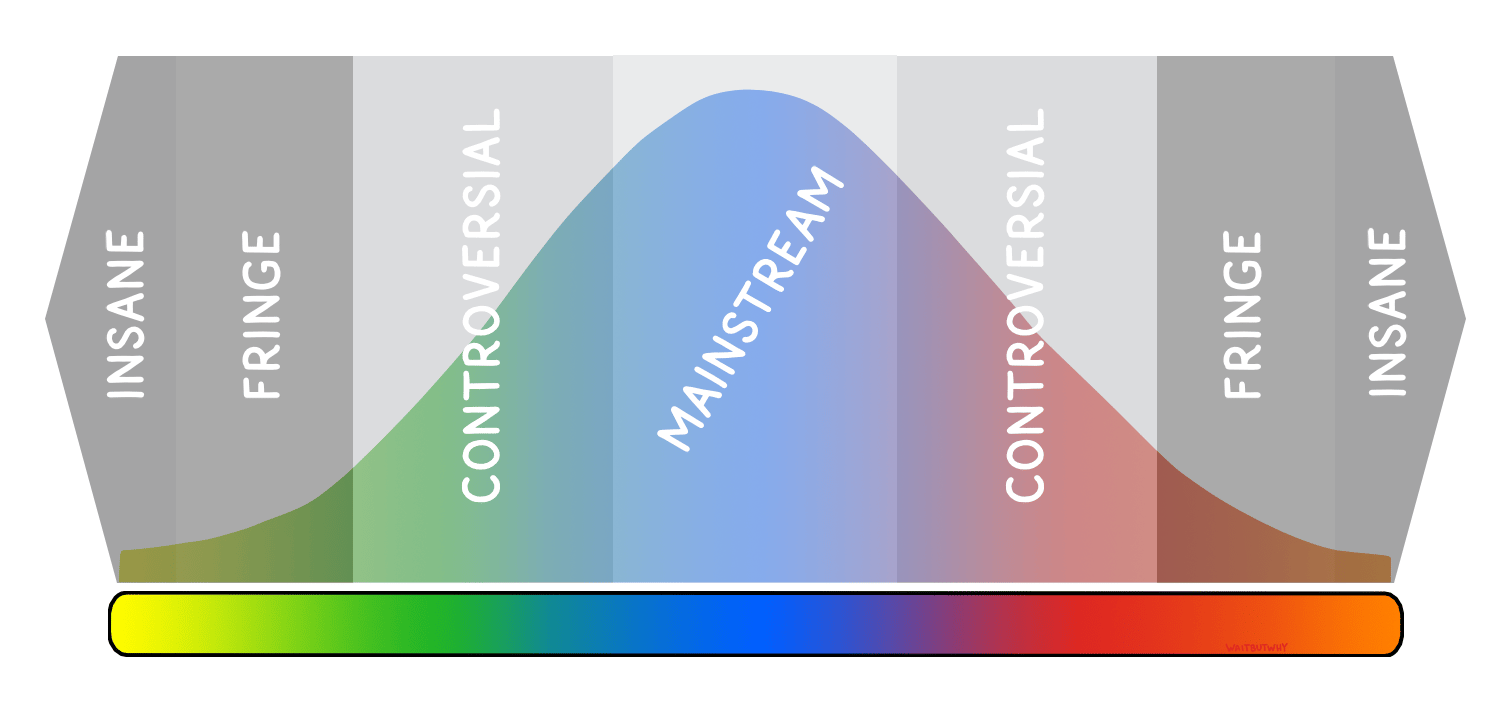

The MPI is Outer Self suppliers selling ideas, via expression, to listening Inner Self consumers. So the Speech Curve is the MPI’s supply curve. And because people tend to be interested in listening to like-minded people, the top of the Thought Pile can serve as a decent proxy for an MPI demand curve.

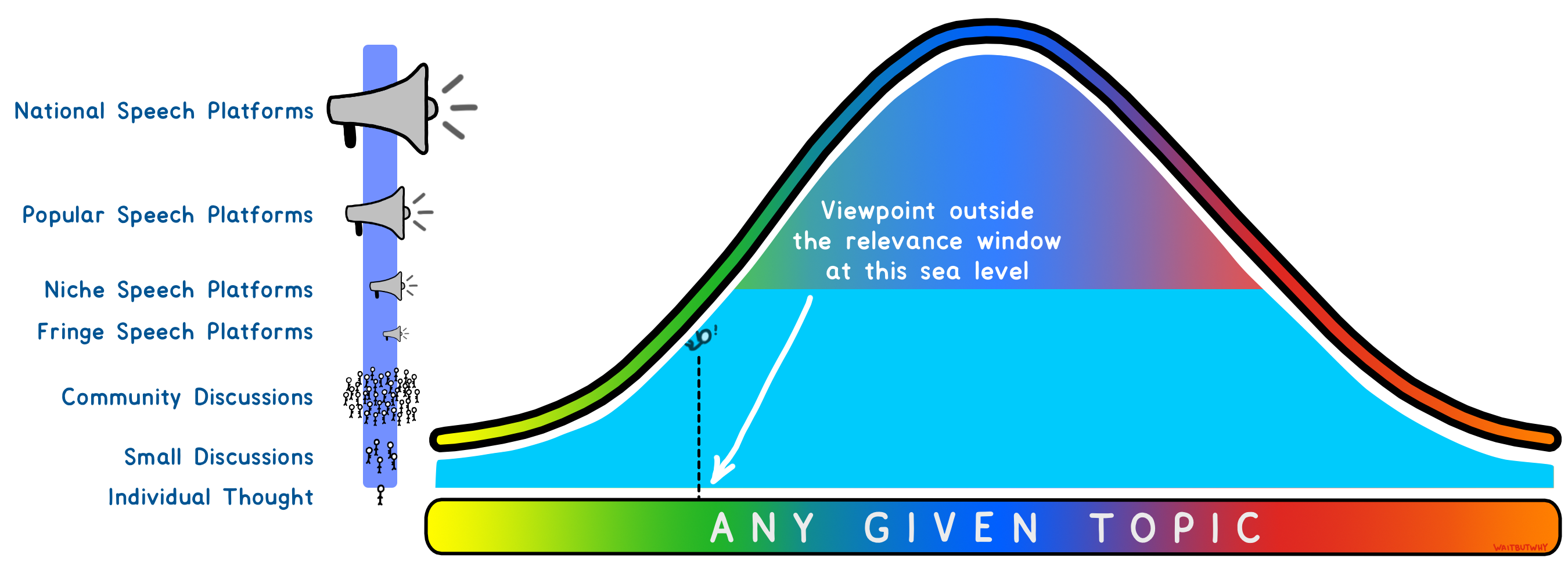

With the First Amendment barring restrictions on expression, attention seekers can take advantage of all parts of the Thought Pile. The most popular viewpoints on each topic reach the largest stages—national media, national politics, pop art—while the supply of less common viewpoints finds some space with the smaller megaphones, like local radio or, today, popular websites or YouTube channels. Even the fringe viewpoints shared by only a small minority of the listener base is satisfied on fringe internet forums or niche podcasts. When the MPI is at equilibrium on a topic with supply and demand matched up, the Speech Curve flops down right on top of the Thought Pile:

The But Wait I Can Think of Examples Where It Doesn’t Look Like That Blue Box

You’re right. In reality, the MPI is far from a perfect market, leaving many topics looking very different than a smooth bell.

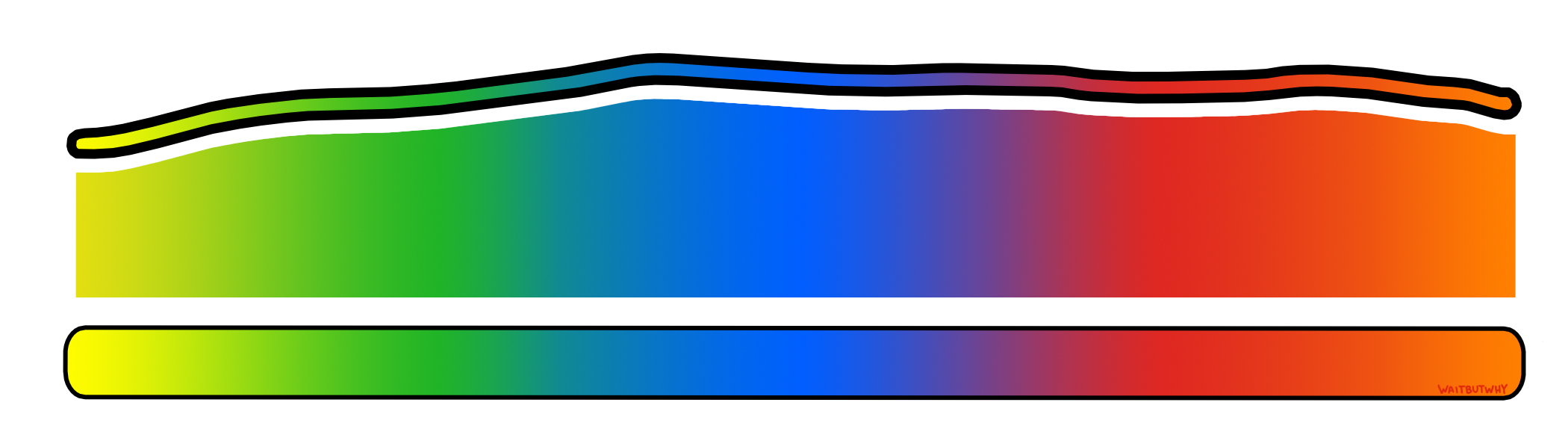

Some topics have a more even distribution of believers across the idea spectrum.

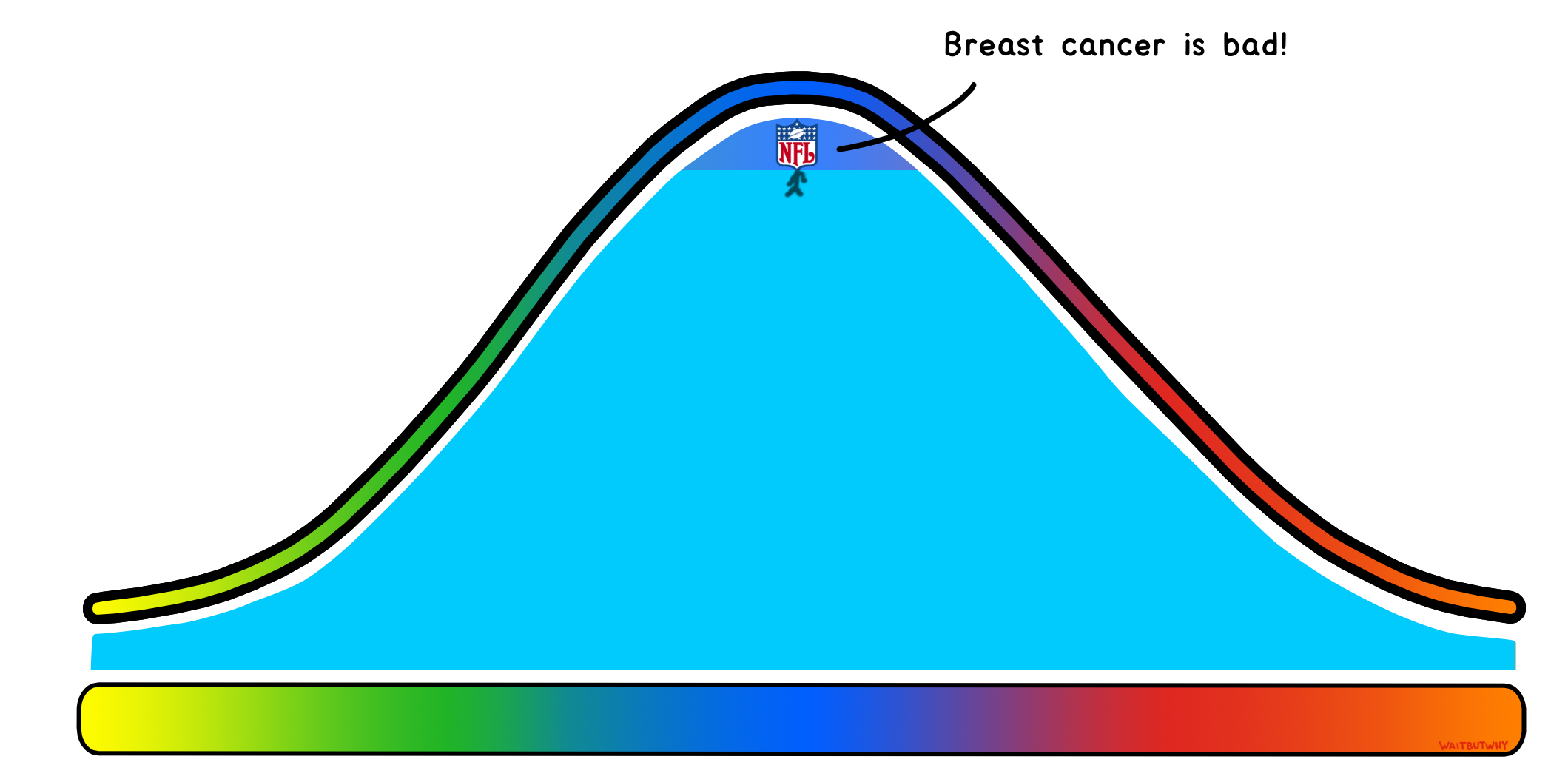

With others, almost everyone is in agreement.

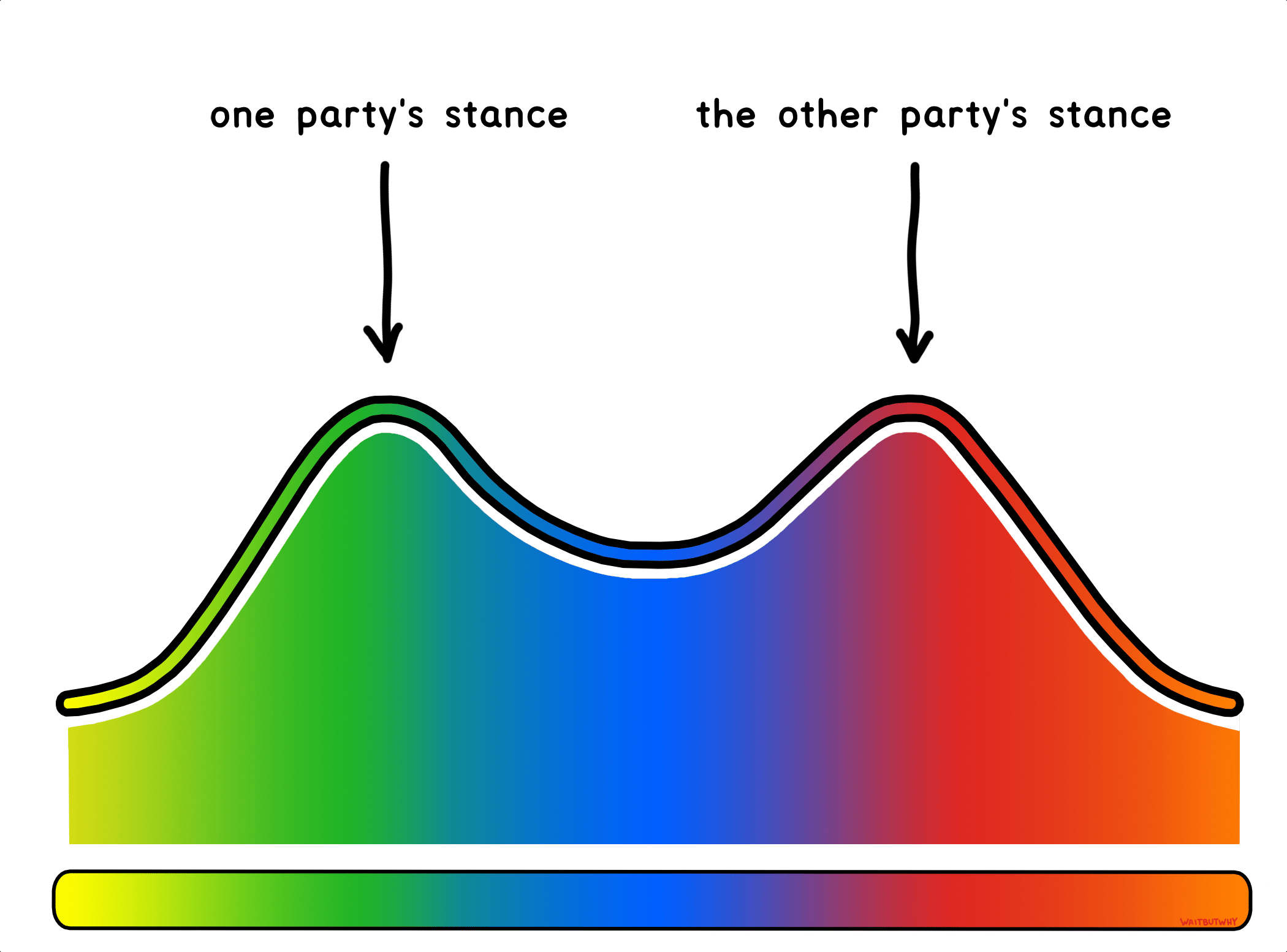

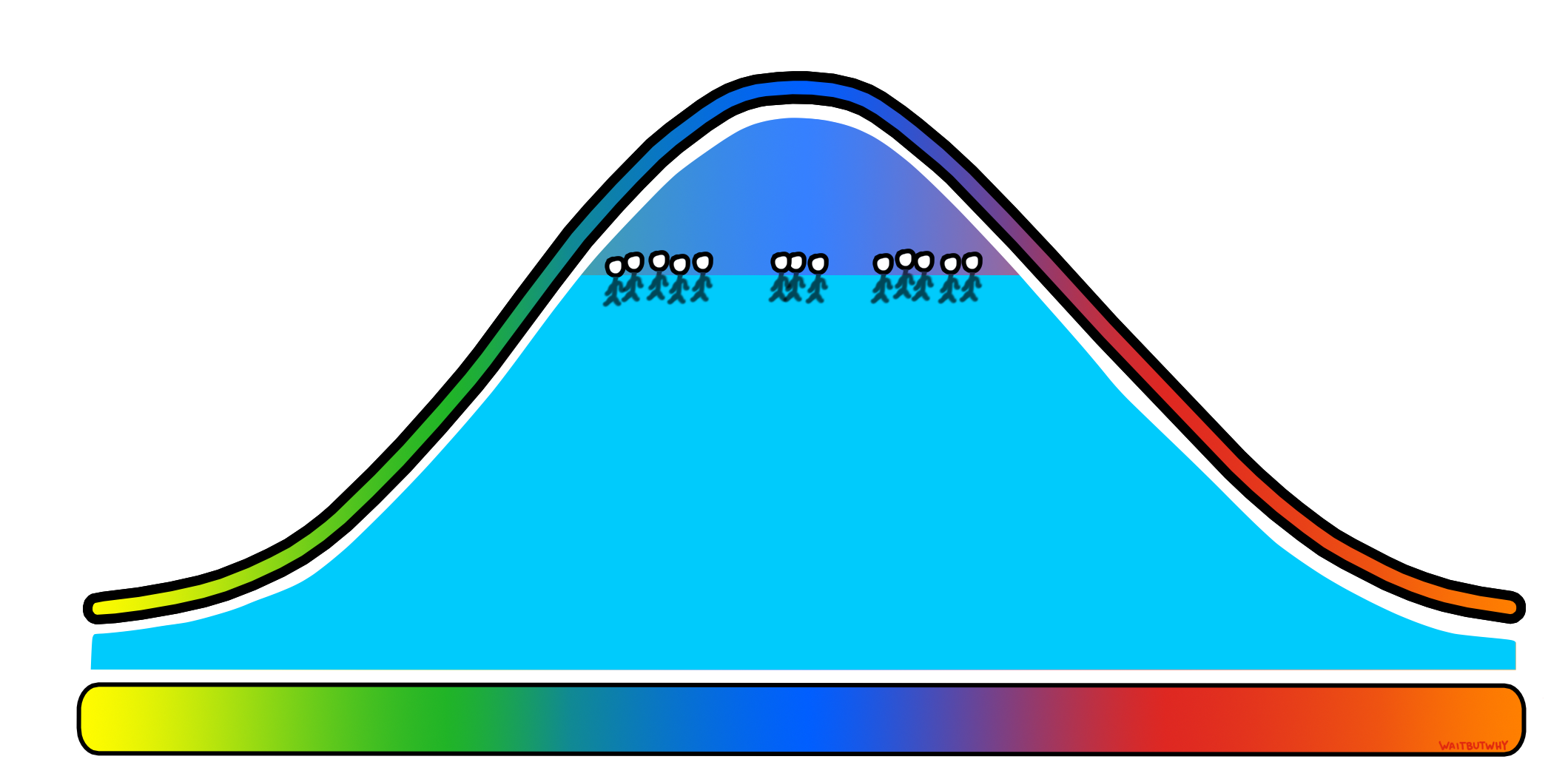

When a topic has become mixed up with a tribal divide, there will be lots of people clumped together into camps.

And sometimes, in spite of the First Amendment, a lot of people are not saying what they think about a certain topic—creating Power-Games-style gaps between the Thought Pile and the Speech Curve like we saw in Hypothetica.

The latter two examples happen when the market is being affected by some external force—usually something going on in the culture. These kinds of marketplace externalities will be a central topic later on in this series. But before we can get into that, we need a strong foundational understanding of how the MPI works when it’s working well. So for now, we’ll be dealing in clean, simplified, perfectly aligned bell curves, so we can understand the basic concepts they represent.

Relevance Windows

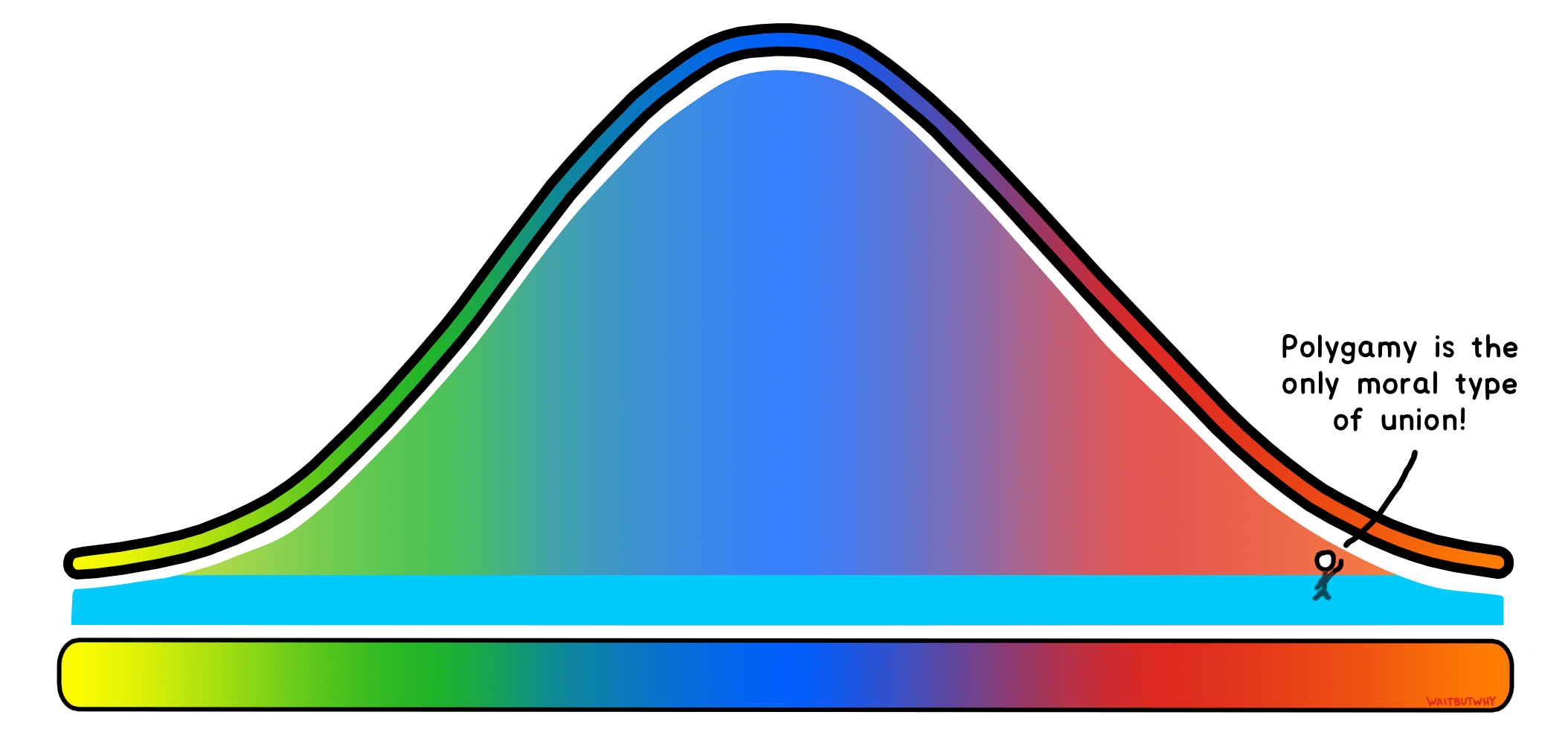

Technically, many thought spectrums can go on endlessly in both directions.

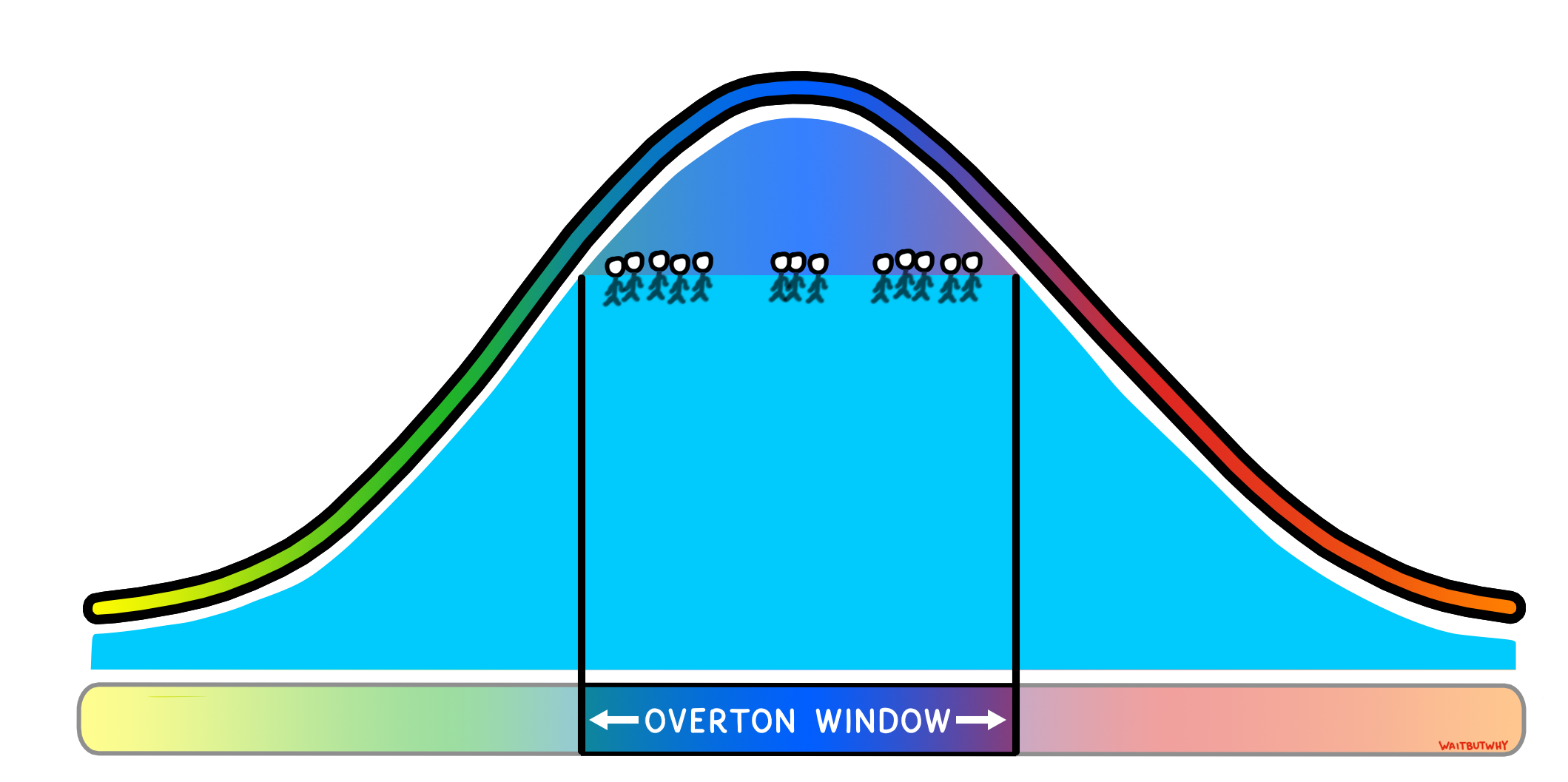

But the MPI has a natural filter to keep discussions within a range it considers reasonable—what we can call a relevance window. The relevance window is a concept we discussed in Hypothetica—the portion of the idea spectrum where listener demand is high enough to support attention on that size stage.

For a speaker who wants to gain or maintain sustained attention on a given size stage, it’s as if the Thought Pile is filled with water up to that level.

If the speaker expresses too many viewpoints outside of the relevance window, the interest level wanes, “drowning” them out of relevance at that level.

Businesses in the economic marketplace think about this kind of “sea level” all the time. If someone wants to build a billion-dollar business, they usually need to be offering a product or service that millions of people want—like, say, jeans.

But if that jeans company decides to stop making jeans and start selling Irish kilts instead, they’ll no longer have enough demand to remain at the billion-dollar-company level, and they’ll drown. To survive with their new niche, they’d need to downsize and embrace being a much smaller company, doing business on a lower tier.

Likewise, a speaker on a large stage with a huge mainstream audience can start focusing on more extreme or obscure ideas, but they’ll probably be downgraded by the market to a stage with a lower sea level.

Down on a lower level, the viable relevance window is wide—which is why you can find small podcasts and YouTube channels and blogs and subreddits focusing on almost any topic or promoting almost any viewpoint you can imagine.

But the MPI imposes a low attention ceiling on them. That’s why someone that requires a gigantic stage and widespread approval to stay afloat, like a massive corporation, will usually keep to the most non-controversial possible expression.

The typical bell curve shape means that as a speaker, you can express far-out viewpoints or you can shoot for a super-high attention platform—but you typically cannot do both.1

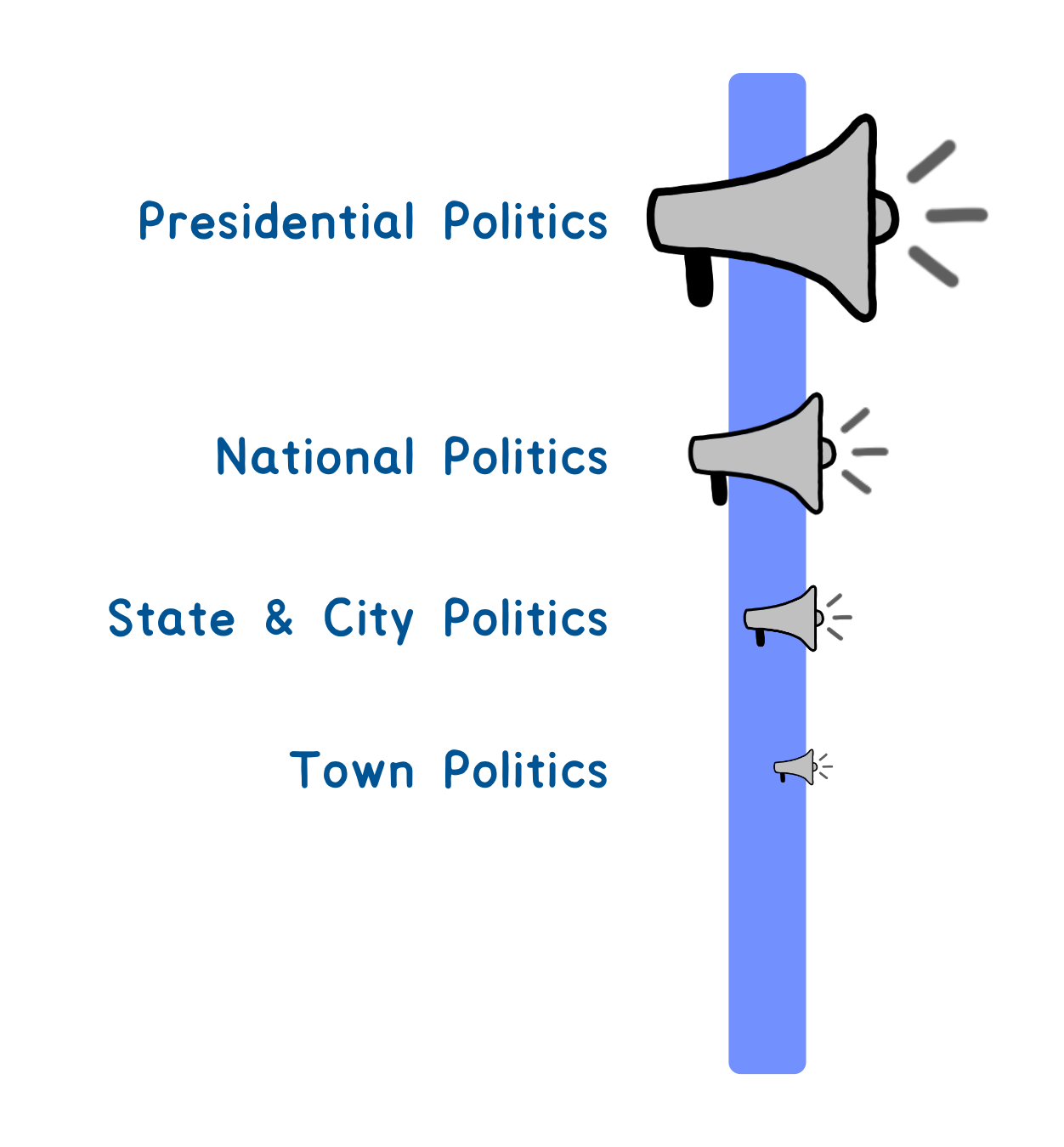

This concept applies to politics too. To win national elections, politicians need to appeal to a significant portion of the entire national Thought Pile, leaving them swimming around at a pretty high sea level.2

Political sea level sets the boundaries of the national politics relevance window, which actually has its own name in political science: the Overton window.

Political sea level sets the boundaries of the national politics relevance window, which actually has its own name in political science: the Overton window.

The Overton window is a newish term—named last decade after late political scientist Joseph Overton—but it’s a concept as old as democracy itself: that for any political issue at any given time, there’s a range of ideas the public will accept as politically reasonable. Positions outside of that range will be considered by most voters to be too radical or too backward or too controversial to be held by a serious political candidate, and holding those positions will render a candidate unelectable.

In the U.S., politicians with presidential ambitions who venture outside of this window won’t appeal to enough voters to contend in a general election—they’ll drown.

But similar to the attention market, the political market spans the vertical tiers.

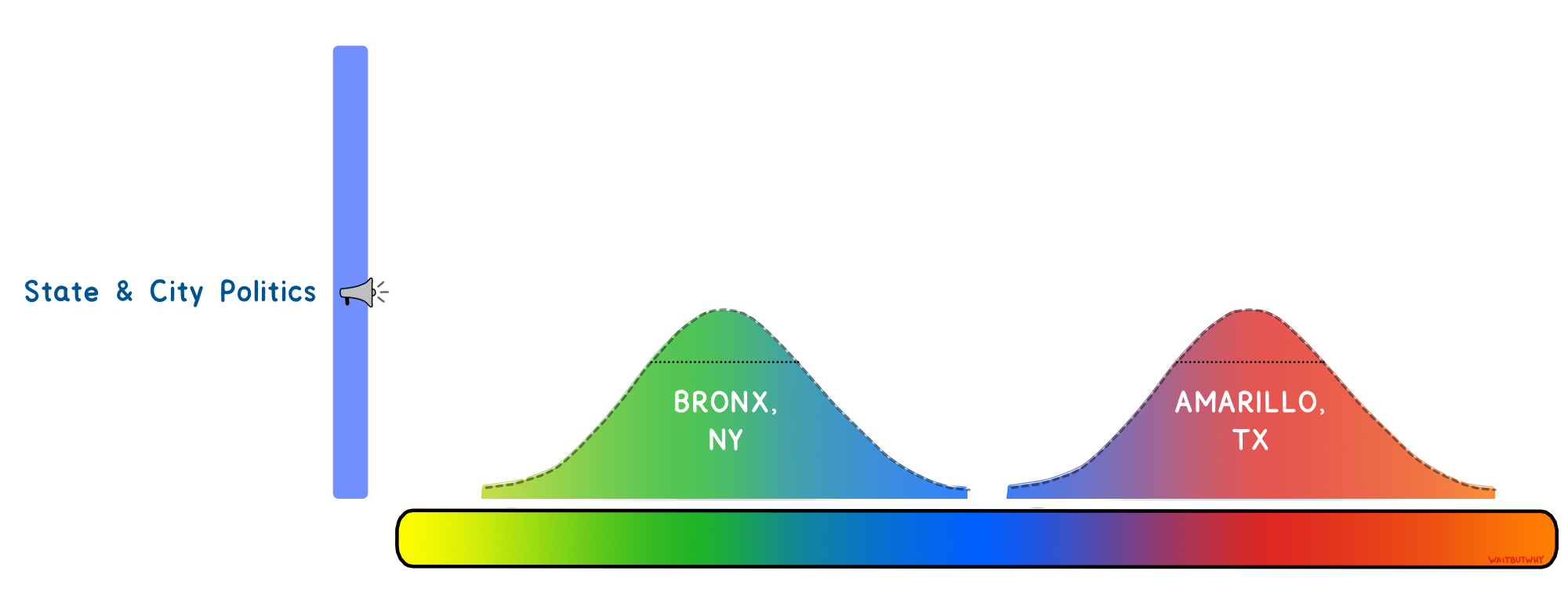

If you’re running for a U.S. congress seat in The Bronx or in Amarillo, Texas, your constituency forms a much smaller Thought Pile that’s located off the center of the idea spectrum.

You still need to win a large percentage of that constituency—so you’re still dealing with a critical relevance window towards the top of your Thought Pile—but that window allows for, and sometimes requires, less nationally mainstream views.

In a totalitarian dictatorship, power flows from the top down. Leaders aren’t beholden to any kind of relevance window—so they go wherever they want along the idea spectrum. But a democracy works the opposite direction—bottom-up—as the leaders are forced to be wherever the Thought Pile wants them to be.

A nice example is gay marriage policy in 2008. According to 2008 opinion polls on the topic in Texas and New York, the Bronx and Amarillo Thought Piles looked something like this:

So it’s not surprising that Mac Thornberry, who was running for congress in Texas’s 13th district, was anti, while Charles Rangel, who was running for congress in New York 15th district, was pro.

The same year, polls showed that the two national parties’ Thought Piles looked something like this:

So it’s equally unsurprising that every candidate running in the 2008 Republican presidential primary—McCain, Romney, Huckabee, etc.—held an anti-gay-marriage stance.

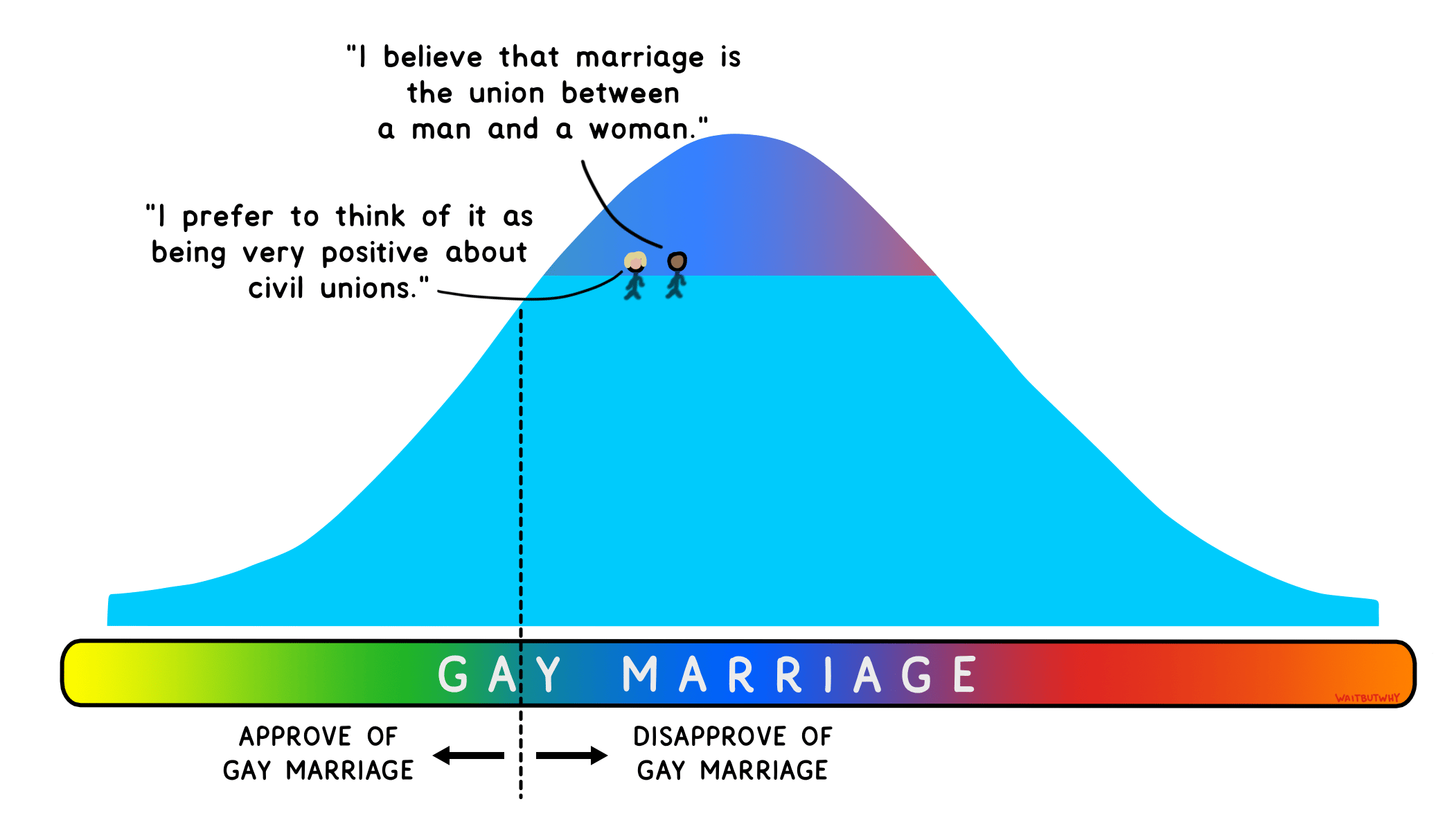

But how about the two frontrunners in the Democratic primary: Obama and Clinton?

The Democratic Thought Pile suggests that they had the liberty to choose their position on gay marriage. But primary candidates are thinking about two Thought Piles—their party’s and the entire nation’s—since after the primary, they’ll also need to win the general election.

And the national Thought Pile in 2008 looked more like this:

The need to win both the primary and general election means politicians are actually bound to an even smaller window—the intersection between their party’s relevance window and the national Overton window. Go too far towards the center and drown in the primary election; go too far away from the center and drown in the general election.

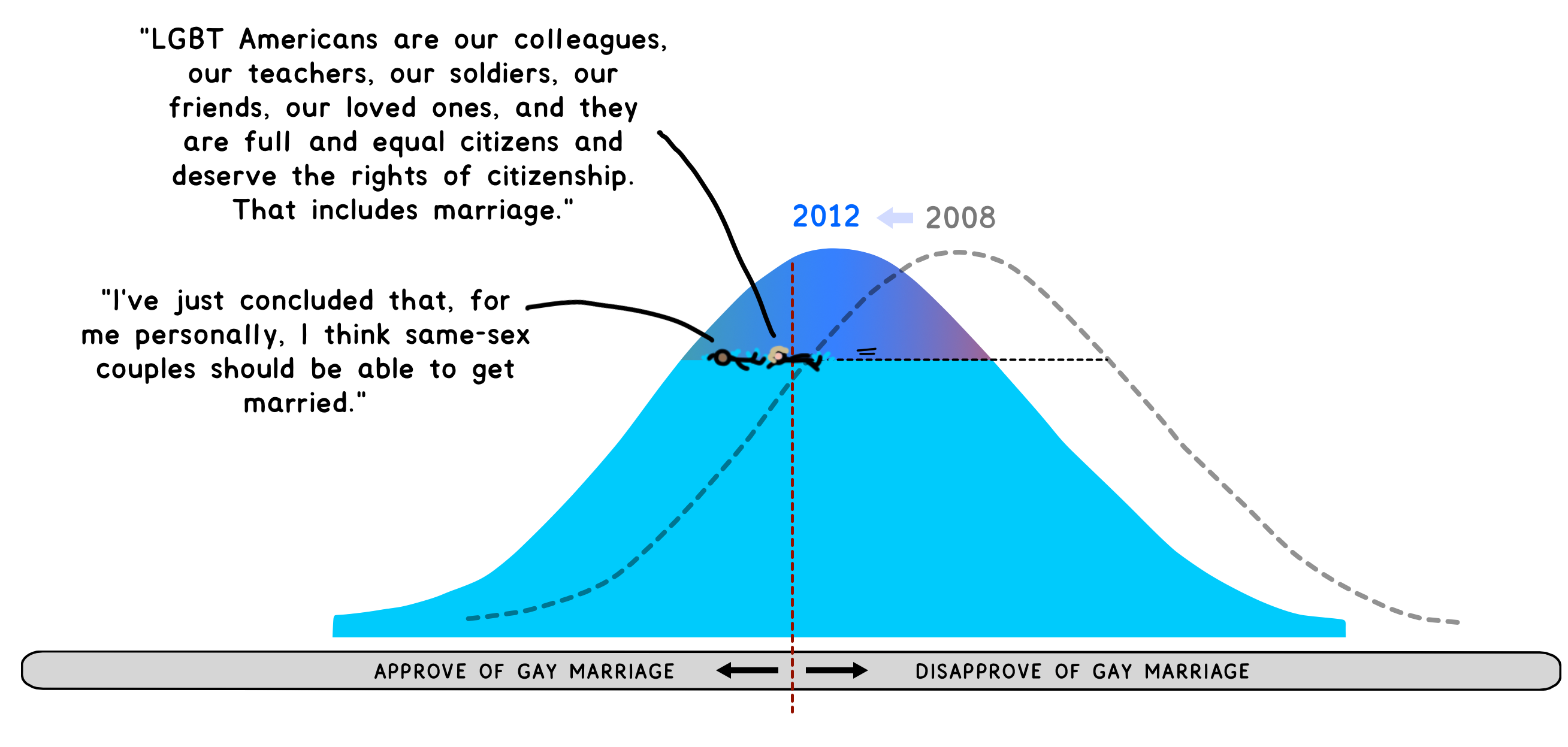

In the 2008 snapshot of the MPI, the pro-gay-marriage stance wasn’t yet inside the Overton window—which is why you heard Obama and Clinton say this:1

With all of this in mind, let’s back up for a second.

What we’ve discussed so far is a basic snapshot of the marketplace of ideas—a picture of what the marketplace looks like at a single moment in time. In reality, there’s a lot of other stuff going on in the MPI—stuff like tribalism and virtue signaling and media manipulation and the cudgel of cultural taboo and other fun things in the pit of hell we’ll be descending into together later in the series. But we’re keeping things simple for now, and the basic concepts of the Thought Pile and Speech Curve—and the relevance windows and attention ceilings yielded by their shapes—is a good starting point.

To most of us, the marketplace snapshot is an intuitive roadmap. Without realizing we’re following any specific roadmap, we’re all subconsciously aware of the marketplace’s supply and demand, its areas of relevance, and its uncrossable lines—and we use this intuition to navigate our way through society. Each subculture, each company culture, each marriage or group of friends is its own little MPI with all of these components in place, and most people abide closely by the various lines and curves—because a culture’s marketplace curves are a roadmap to popularity, and diverting off that map is often a roadmap to ostracism. Wannabe comedians and writers and podcasters and artists and entrepreneurs have the shape of their target audience’s marketplace curves on the forefront of their minds—because it’s a roadmap to acquire the precious attention and respect necessary for success. Politicians have entire teams working day and night to suss out the dimensions of the idea marketplaces of their party and of the country, because for them, it’s a career survival instruction manual.

And if that’s what you want—popularity, attention, survival—then it makes sense to use the current marketplace curves as guidelines.

But what if you want more?

Abiding by the existing shape of the MPI is an exercise in mimicking the status quo. It’s taking what society’s brain is already thinking and jumping into the flow to try to get a piece of the action. It’s being a cook.

Trying your best to meet existing demand for ideas is trying your best to preach to the choir—to have your voice ascend in the marketplace on a vertical column of attention by preaching a little better than the other preachers—by offering a little crunchier version of the same expression carrot they’re already eating.

There’s nothing wrong with doing any of that. But it’s not leadership.

Leadership is, by definition, leading people away from where they already are. If you’re preaching to the choir, you’re not leading anybody anywhere.

When you’re zoomed in on a snapshot, markets are distribution mechanisms that allot coveted, limited resources like wealth or attention. But then we remember the cool thing about markets: when a market is working well, the cumulative effect of all the activity is a giant forward arrow.

When you back up and look at the bigger picture, the economic market is a progress machine. When you apply the axis of time to the economy, you see that each market snapshot is a thin slice of a forward progress arrow of technology, of innovation, of efficiency, of prosperity.

Over time, the MPI generates its own giant progress arrow: the growth of both knowledge and wisdom. When a country can think for itself, it gets both smarter and more mature as it ages.

Every individual competing in the economic marketplace is, to some extent, contributing to the big progress arrow. But the chefs—those pushing the mainstream out of their comfort zone—are the primary drivers of change. The entrepreneurs who, instead of building a better hotel, build Airbnb. The tech moguls who, instead of building a better flip phone, build the iPhone. The employees who challenge the company’s conventional wisdom instead of kowtowing before it.

Likewise, if you want to do more than preach to the choir in the MPI—if you want to help drive knowledge or wisdom forward—you’ll need to make the jump from the benign attention market to the brutal influence market. You have to roll up your sleeves and go looking for the far less pleasant and far less willing kind of audience—the audience who doesn’t agree with you—and tell them things they don’t like hearing.

You’ve got to do something a thousand times harder than confirming people’s beliefs and validating their identities—you have to change people’s minds.

Mind-Changing Movements

At any given point in time, there will be a wide range of what the people in an MPI believe to be true or good. But the ideas that carry the most power will be those held by the most people—the mainstream ideas.

Typically, the mainstream ideas are what will be taught in schools, what will appear most often in art, what will dictate broad cultural norms, and what will limit the stances held by national politicians. Even though plenty of individual citizens will disagree with them, the ideas at the top of the Thought Pile are what the big communal brain “thinks” at any given point in time.

To make real, meaningful change in a country, you have to change the big brain’s mind.

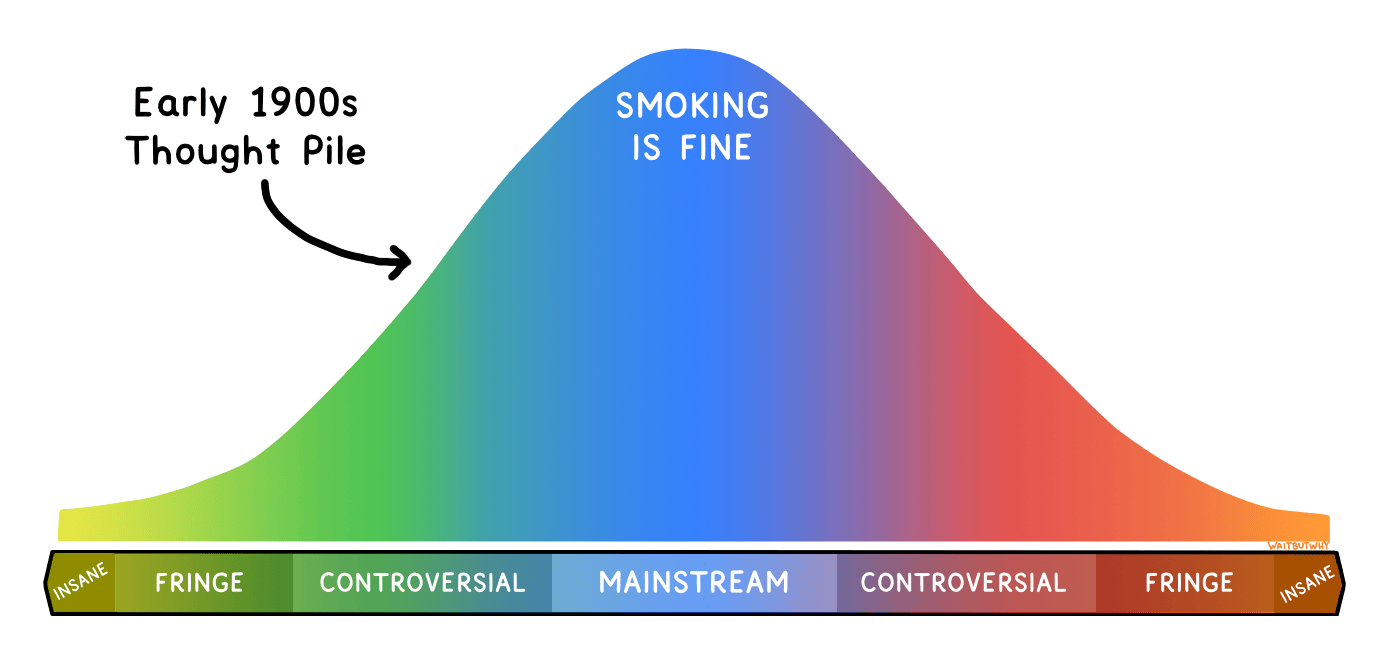

The modern cigarette was invented in the 1880s and exploded in popularity in the U.S. in the first half of the 20th century. Americans went from smoking an average of 50 cigarettes per adult per year in 1880 to over 2,000 by the mid-1940s.2 Throughout these decades, it was a mainstream view among Americans that smoking was a relatively harmless habit.

The communal U.S. brain believed that smoking was harmless, and everything else fell in line behind that belief. Ads portraying cigarettes in a positive, beneficial light were everywhere. Cigarettes were culturally cool and commonly associated with movie stars and other icons. You could light up in airplanes, restaurants, offices, hospitals, and most other places. Where the big brain goes, everything else follows.

But then there was this other idea out in more controversial territory:

This viewpoint was born in the early part of the century, when research started to appear linking smoking to all kinds of health problems.

People who had come to believe that smoking is dangerous started talking about it.

Preaching to the choir is generally received well, met with a reaction of love or approval. When your mission is to make people feel great about what they already believe, the MPI is usually a pleasant, friendly place.

But when you tilt the angle of that megaphone towards people who don’t agree with you, the MPI becomes a gauntlet.

The MPI gauntlet is especially treacherous for ideas outside the mainstream. People don’t like having their beliefs challenged or their favorite habits disparaged. Companies profiting off the status quo really don’t like dissenting viewpoints. So the new, anti-smoking ideas were attacked from all sides.

Most claims to truth that aim to debunk the mainstream perception of reality turn out to be wrong—and the MPI gauntlet is great at exposing their wrongness. Sometimes a false idea can make a run at it for a while, but the further it gets in widespread adoption, the more viciously the MPI attacks it. When false claims to truth go up against a marketplace free to criticize them, the marketplace almost always wins. Eventually, the falsehoods are shown to be wrong so clearly by the marketplace that all but the most stubborn zealots stop believing them.

But the gauntlet provides a second service. Scattered throughout the haystack of bogus claims are needles of actual truth. The gauntlet, acting selfishly, attacks all claims to truth—hay and needle. When it attacks hay, it exposes the claim as hay. But when it attacks a needle, the needle stands strong. The more the needle of truth withstands the gauntlet’s attacks, the more people begin to adopt the viewpoint as their own. After enough attacks from the gauntlet, a needle still standing is exposed to be true. By no intentional goodwill, the same gauntlet that exposes falsehoods also exposes truth. The two services make the nastiest side of the MPI—the relentless gauntlet—an efficient truth-finder that sifts through hay and identifies the needles.

So the gauntlet went full force on “smoking causes cancer,” hammering it from every possible angle, trying to expose it as (or at least frame it as) a fear-mongering strand of BS hay.

And for a while, the attacks were effective. Forty years after the early evidence surfaced linking smoking to cancer, a 1954 Gallup survey found that 60% of Americans answered “No” or “Unsure” to the question “Does smoking cause lung cancer?” And in 1953, 47% of Americans smoked cigarettes—including half of all doctors.3

But the gauntlet can only hold off a truth needle for so long, and the anti-smoking claims didn’t fade away—they only got louder.

In 1964, the U.S. Surgeon General issued a public report on smoking for the first time, outlining the negative effects. As more and more evidence began to pile up about the dangers of second-hand smoke, more people in the marketplace began to protest cigarette smoking being legal in indoor spaces. Parents whose minds had changed about cigarettes became more likely to prohibit their children from smoking. The culture started to turn against smoking, lowering the prevalence of the cigarette in TV shows. Politicians, noticing the shifting tide of public opinion, began to outlaw cigarette ads, require cigarette companies to display warnings on their labels, and ban smoking in enclosed spaces like restaurants and airplanes, making a smoking habit increasingly inconvenient.

As the big U.S. brain’s answer to “Does smoking cause lung cancer?” changed from “No” to “Yes”4—

—the percentage of Americans who smoked dropped from 47% in 1953 to 14% in 2017.5

The cigarette story is a story of the MPI doing its job. It’s a story of a needle of truth rising up from a haystack on the fringes of the big brain’s consciousness and piercing its way through a century-long barrage of gauntlet attacks until it had conquered the Thought Pile mountain and become the mainstream, status quo viewpoint.

The “smoking causes cancer” viewpoint didn’t conquer the Thought Pile by climbing it, but rather by pulling the Thought Pile to where the viewpoint had always been, along an Idea Spectrum that itself never changed—and in the process, pulling the Thought Pile away from the “smoking is fine” viewpoint.

And as the “smoking causes cancer” needle coaxed the Thought Pile to slide itself along the Idea Spectrum towards it, the Thought Pile dragged everything else with it—culture, politics, laws, and behavior. All of this happened against the tremendous force of a large industry’s fight for survival—because the little needle had truth on its side, and in a free MPI, truth prevails.

For reasons we discussed in Part 1, we’re a species that isn’t great at truth. We’re built to believe convenient delusions, not to be accurate. Given this fact about us, the MPI isn’t just a way for a large group of people to work together to find truth, it’s the only way for them to do it. As author Jonathan Rauch points out, when someone like Einstein declares his theory of general relativity, there literally is no way to tell if he’s a genius or a madman until the “global network of checkers,” as Rauch puts it, attacks the theory from all angles, looking for holes, and continually fails.

Little Lulu from Part 1 did the best she could, using her own life experience and her own sense of reason, to turn her mind into a truth filter at that berry bush. The MPI carries out Lulu’s process on an industrial scale, in which all the conflicting misconceptions and motivations come together in a great clash, and in the rubble, truth is left standing.

The same marketplace that makes its communal brain more knowledgeable also makes it wiser.

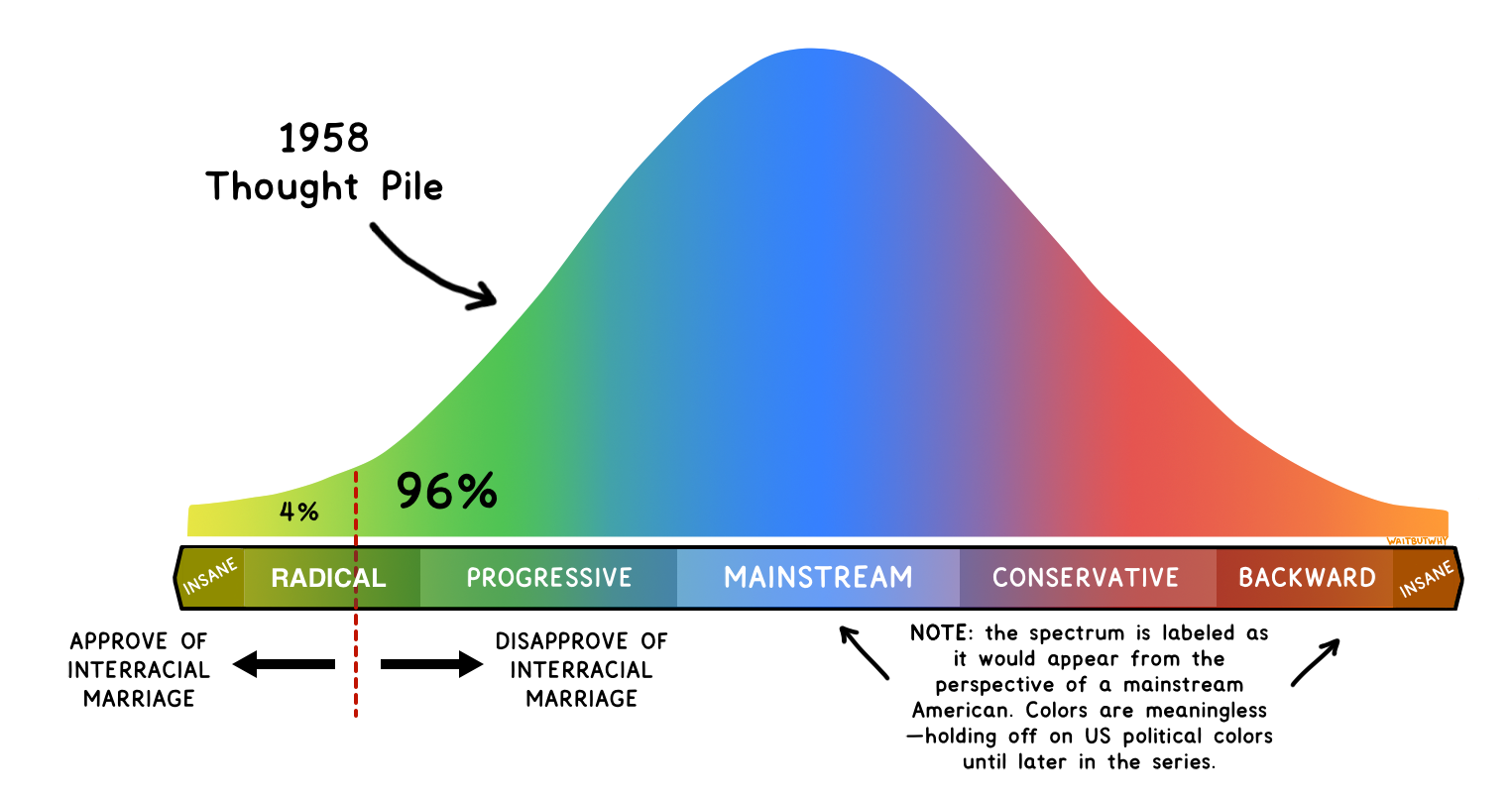

In 1958, 96% of Americans disapproved of interracial marriage.6 The 4% who approved were on the far fringe:

Right next to the U.S. brain’s perception of what’s right and wrong factually is its perception of what’s right and wrong morally. Both knowledge and wisdom are ever-evolving works in progress, and in both cases, the nasty MPI gauntlet is the mechanism that drives that change.

In the case of the U.S. brain’s views on interracial marriage, things have changed very quickly, at least by sociological standards. By 2013, only 55 years after 96% of Americans disapproved of interracial marriage, that percentage had dropped to 13%. A complete 180.

If fringe truth claims are a pile of nonsense hay with a few truth needles inside, fringe claims about morality are a pile of dogshit dotted with a few diamonds of wisdom. Most of what the fringe has to say will always be wrong, because the fringe is cluttered with the least knowledgeable and least wise among us. But scattered within that crowd are often the very wisest people too.

In 1958, almost every reasonable person in the U.S. thought interracial marriage was an immoral thing. Today, we see this as a failure of wisdom. The 4% who disagreed with them were the wisest people of all when it came to this topic. Their ideas were the diamonds in the dogshit.

The MPI is not kind to factual hay, and it’s even less kind to moral dogshit. While those who believe fringe, foolish moral claims are usually positive that those claims are diamonds, the MPI has a bright flashlight, and a sensitive nose, and dogshit doesn’t last long in the gauntlet. But when the rare diamond does enter the marketplace from the fringe, the more light that shines on it, the brighter it gets. In a half century, the small group of activists wise enough to see that interracial marriage bans were wrong, ridiculous, and unconstitutional, shouted their unpopular ideas into the MPI, igniting a mind-changing movement that spread until the change of mind had reached the center of the U.S. brain’s consciousness.

We can look at this story on our idea spectrum.

Starting a mind-changing movement is like starting a fire with flint—it’s laborious and sometimes not even possible. But when it gets rolling, it can spread like a forest fire. The history of interracial marriage in the U.S. is another story about the power of a free marketplace of ideas. It’s the same power that changed the U.S. brain’s mind about duels, about slavery, about child labor, about women’s suffrage, about business monopolies, about segregation, and the same power that’s currently working out what it thinks about animal rights, and bioethics, and online privacy, and ten other things, many of which seem right now like fringe dogshit to 96% of us.

The people who argued for cigarettes and against interracial marriage weren’t, on average, worse people or stupider people than today’s Americans—just like the medieval scientists who believed the solar system was geocentric weren’t less intelligent than today’s scientists. Like any individual, a society grows up over time by reflecting on its experience, reconsidering what it believes, and working to evolve for the better. And like an individual, this evolution takes place within society’s mind. A society’s mind is its marketplace of ideas, and the freer, more open, and more active that marketplace is, the sharper and clearer the giant mind is and the faster the pace of societal growth.

The Extra Thoughts on Leadership Blue Box

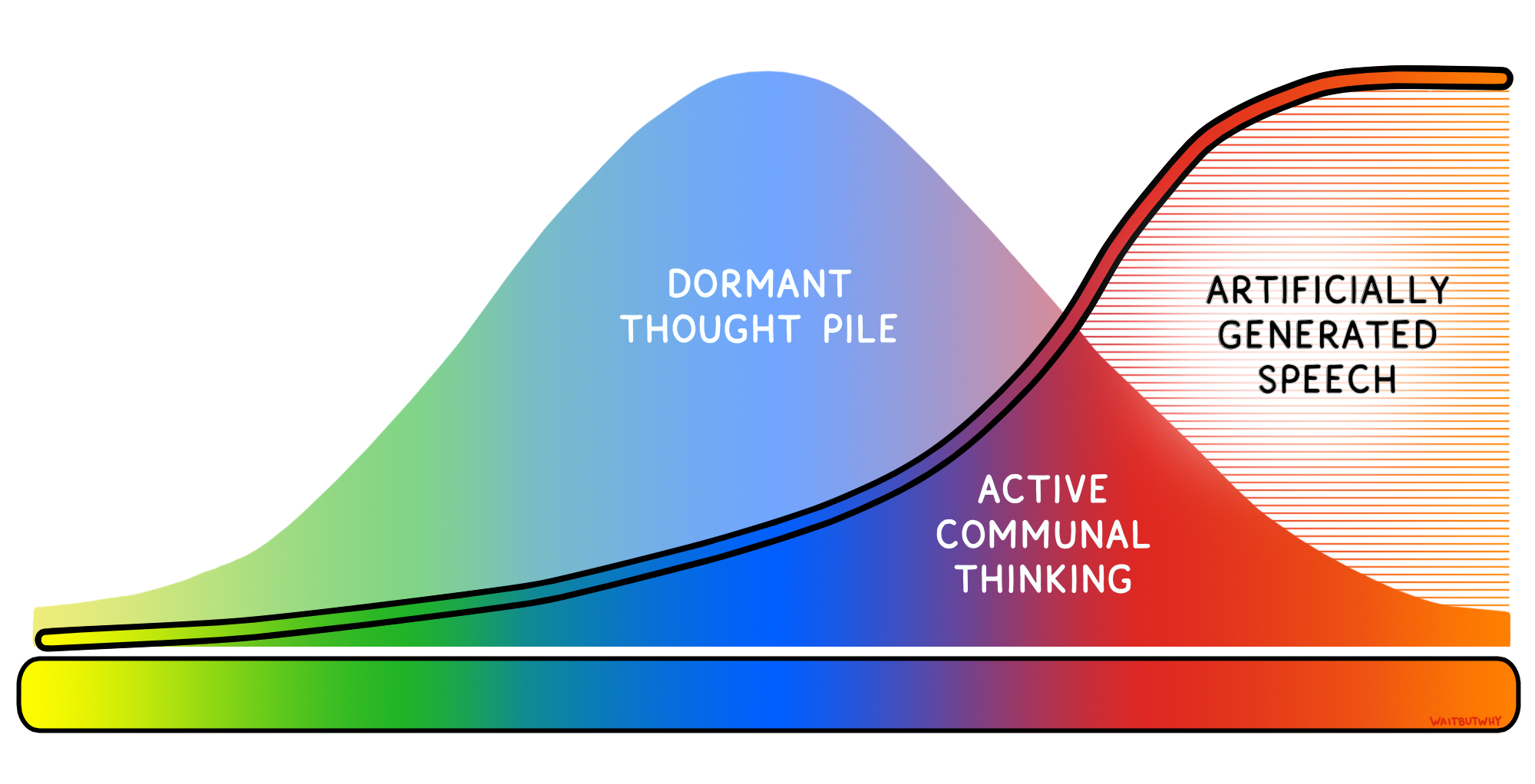

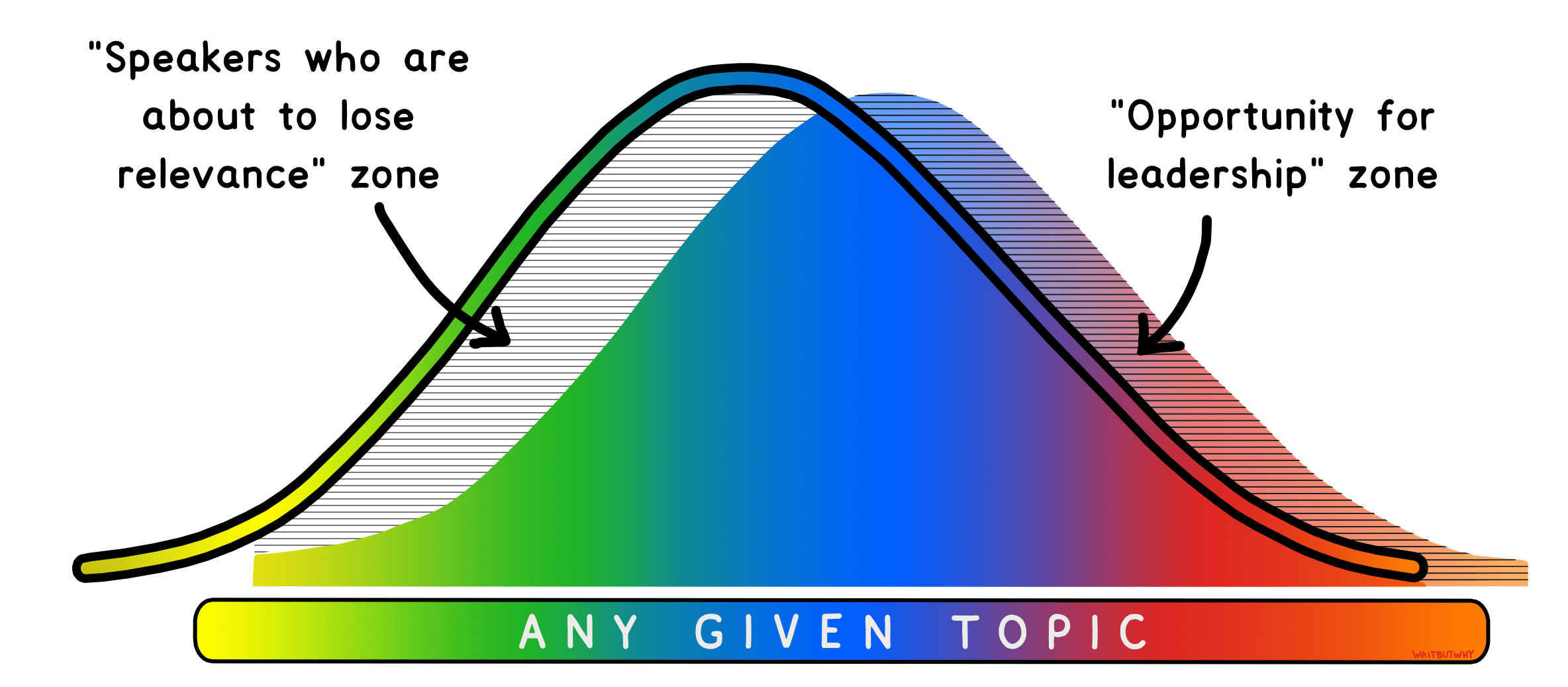

All leadership is hard, but some is harder than others. In the above examples, I left out the Speech Curve and just focused on the Thought Pile for simplicity. But in reality, the Speech Curve and Thought Pile move together, each at times being the leader that pulls the other one behind it. In instances when the Thought Pile is the leader, it means that the big brain has quietly changed its mind about something, through lots of small conversations—but no one quite realizes yet just how sweeping a shift has taken place, so people are still timid to say out loud what everyone is thinking. It looks something like this:

In a case like this, the Speech Curve is outdated for a period of time until people perceptive enough to see the Thought Pile’s real location and courageous enough to trust their instincts start speaking up—venturing into this zone on the right:

If these bold speakers are wrong about where the Thought Pile is, they often end up in trouble, penalized by the market. But when they’re right, they’re handsomely rewarded. They become iconic stand-up comedians, best-selling authors, and election-sweeping politicians. One example that pops to mind is Obama being like, “Yeah duh I smoked pot. Smoking pot is fun.” The widespread assumption at the time was that saying something like that would sink a politician (which is why a few election cycles earlier, Clinton pretended he never inhaled)—but Obama was savvy enough to see that the Thought Pile had shifted and the Speech Curve was lagging behind. And it turned out to be a boost for his popularity.

If these bold speakers are wrong about where the Thought Pile is, they often end up in trouble, penalized by the market. But when they’re right, they’re handsomely rewarded. They become iconic stand-up comedians, best-selling authors, and election-sweeping politicians. One example that pops to mind is Obama being like, “Yeah duh I smoked pot. Smoking pot is fun.” The widespread assumption at the time was that saying something like that would sink a politician (which is why a few election cycles earlier, Clinton pretended he never inhaled)—but Obama was savvy enough to see that the Thought Pile had shifted and the Speech Curve was lagging behind. And it turned out to be a boost for his popularity.

Saying what everyone is thinking but not saying is a form of leadership. It formalizes a Thought Pile shift that has already happened, clearing the way for everyone else to start saying those things too. A few bold speakers with big platforms are usually all it takes for the whole Speech Curve to shift and realign with the Thought Pile.

Then there are the times when the Speech Curve leads the Thought Pile. This is when someone has the nerve to go here:

This is even riskier than saying something that you suspect is already within the Thought Pile. It will for sure be met with resistance, and there’s a strong chance the speaker will be zapped out of relevance by an angry Thought Pile. But if the speaker is good enough—and if they have truth or wisdom on their side—they may be able to change people’s minds and pull the Thought Pile over toward their viewpoint. Changing minds is the harder kind of leadership. It requires even more courage than the “say what everyone’s thinking” kind, and if it succeeds, it’s even more impactful.

Both kinds of leadership are incredibly important. They’re both the work of people who have the guts to reason from first principles and act on that reasoning. And most movements are probably the result of a bit of both forms of leadership. In this way, the Thought Pile and Speech Curve are a tag team, each taking the reins at times when the other is lagging behind, working together to drive the country’s evolution.

The MPI is an attention market, a knowledge market, and a wisdom market—all rooted, like the economic and political markets, in the fundamental American freedom-fairness compromise: everyone has an equal opportunity to compete, but no one has a right to succeed. Anyone is free to run for office, start a business, express their opinions, or become an activist—but to actually acquire power, wealth, attention, and influence, you have to earn it from your fellow citizens on the playing field.

But Value Games markets are fragile, and they rely on clear rules. The status quo has a fierce survival instinct, which is why leaders in any market will be met with resistance—and what matters most is the type of resistance. In the Power Games, with the looming threat of imprisonment or execution for saying something unpopular with the wrong people, the opponents of cigarettes and the proponents of interracial marriage may have never spoken up in the first place. But the Constitution alters the rules of the game, taking the exact same selfish resistance and transforming it from a gauntlet of harmful cudgels into a gauntlet of harmless criticism, limiting it to attacking the dissent itself, not the dissenter. This kind of resistance, rather than repressing fringe viewpoints, tests them—forming a filter that pushes falsehoods and foolishness down and lifts truth and virtue up. In the same way that a free economic market harnesses human selfishness and points it toward progress and innovation, a free marketplace of ideas transforms selfishness into a compass that points the country in the direction of knowledge and wisdom.

Which brings me back to Obama and Clinton and 2008.

Jonathan Rauch, the author I mentioned earlier, is also a gay activist. He describes what it was like to be gay in the U.S. in 1960:7

Gay Americans were forbidden to work for the government; forbidden to obtain security clearances; forbidden to serve in the military. They were arrested for making love, even in their own homes; beaten and killed on the streets; entrapped and arrested by the police for sport; fired from their jobs. They were joked about, demeaned, and bullied as a matter of course; forced to live by a code of secrecy and lies, on pain of opprobrium and unemployment; witch-hunted by anti-Communists, Christians, and any politician or preacher who needed a scapegoat; condemned as evil by moralists and as sick by scientists; portrayed as sinister and simpering by Hollywood; perhaps worst of all, rejected and condemned, at the most vulnerable time of life, by their own parents. America was a society permeated by hate: usually, it’s true, hateful ideas and assumptions, not hateful people, but hate all the same. So ubiquitous was the hostility to homosexuality that few gay people ever even dared hold hands in public with the person they loved.

In a Power Games country, a topic like gay rights, considered deeply offensive to most people in 1960, almost certainly would have been censored. By censoring anything it considers dogshit, the society also censors that critical wise 4% that drives most of the growth.

But in a U.S. hell-bent on free speech, Rauch tells the story of how things changed:

In ones and twos at first, then in streams and eventually cascades, gays talked. They argued. They explained. They showed. They confronted. … As gay people stepped forward, liberal science engaged. The old anti-gay dogmas came under critical scrutiny as never before. “Homosexuals molest and recruit children”; “homosexuals cannot be happy”; “homosexuals are really heterosexuals”; “homosexuality is unknown in nature”: The canards collapsed with astonishing speed.

What took place was not just empirical learning but also moral learning. How can it be wicked to love? How can it be noble to lie? How can it be compassionate to reject your own children? How can it be kind to harass and taunt? How can it be fair to harp on one Biblical injunction when so many others are ignored? How can it be just to penalize what does no demonstrable harm? Gay people were asking straight people to test their values against logic, against compassion, against life. Gradually, then rapidly, the criticism had its effect. You cannot be gay in America today and doubt that moral learning is real and that the open society fosters it.

It took a while to get there, but by 2008, the U.S. brain had given both the truth and wisdom regarding homosexuality a lot of reflection, and it had changed its mind considerably on the topic.

But as we were reminded above, it hadn’t quite changed its mind on gay marriage yet.

Sensing that the pro-gay-marriage stance was still below political sea level, Obama and Clinton decided to pander to the status quo beliefs and play it safe.

But a mind-changing movement had caught fire and the national Thought Pile was on the move. Only four years later, things were here:

And in a wild coincidence, Obama and Clinton’s views on gay marriage had both evolved:8

The Supreme Court had undergone the same sudden coincidental change of heart, and in 2015, they voted to legalize gay marriage across the country.

While most of us are busy arguing about whatever’s being debated within the Overton window, big picture change is being driven by a second set of battles happening outside the window—battles about exactly where the edges of the window lie. Or as Overton’s think tank puts it, “the ongoing contest among media and other political actors about what counts as legitimate disagreement.” In this second set of battles, proponents of a policy outside the Overton window fight to simply get their policy into the window—that’s the hard part. Then they can worry about winning the inevitable battle over that policy that will ensue within the window. Meanwhile, opponents of that policy will fight fiercely to keep the policy outside the window, where it’s deemed unacceptable to even be debated. That’s the best way to prevent it from happening.3

If you live in a democracy, and you’re not zoomed out far enough, you might look at the politicians running your government and mistake them for your leaders. In the short term, sure, they jostle with each other over the country’s policies and steer the country on the international stage. But with a step back, the real long-term leader of a democracy is the giant communal brain of the citizen body. Politicians are all about principles…as long as those principles fit on the top of the country’s Thought Pile, safely inside the Overton window. But when that Thought Pile moves, like it did on the topic of gay marriage between 2008 and 2012, politicians drop everything and start swimming.

This is no criticism of politicians—being a small-picture leader and a big-picture follower is the politician’s survival requirement. It’s simply a reminder that change in a country like the U.S. starts at the bottom and works its way up to the top. It starts with brave citizens willing to say unpopular things in public. With the right idea and a lot of courage, a single person can spark a mind-changing movement that gains so much momentum, it moves our beliefs and our cultural norms, which in turn moves the Overton window, which moves policy, which moves law.

Whenever a citizen of a democracy speaks up in a classroom or town hall, writes an op-ed, makes a movie, tweets a tweet, or yells something out on the street, they’re sending an idea out into the great network—firing a little neural impulse into the workings of the larger system. Every citizen, whether they realize it or not, is a neuron in the mind of a giant organism, and what they do and say in their lifetime contributes to who that organism is, even if only a little bit.

But all of this only works because of free speech. All of those Thought Piles only ooze along the idea spectrum with a mind of their own because they’re protected from above by the broad arc of a free and protected Speech Curve.

It’s easy to see why free speech is often referred to as not just a right but as the fundamental right on which all other rights are based.

Free speech allows the precious resource of attention to be allotted the Value Games way instead of being doled out by the powerful and high-status at their whim.

Free speech gives citizens a way to resolve conflicts with words instead of violence. When ideas can go to battle against each other, people don’t have to.

Free speech gives power to the powerless. It’s never easy being in the minority in any country. The rich are protected and empowered by their money, the elite by their connections, the majority by their vote. A minority population is often helpless. But free speech gives the powerless a voice—an ability to launch a mind-changing movement that wins over the majority and makes the country better for themselves.

The free speech of individual citizens is the free thought of the communal citizen body, and the singular right that lets hundreds of millions of minds link together into a giant network that can learn, grow, and think as one. Society is driven by the stories we believe, and free speech hands authorship of those stories over to the people themselves.

And it’s for all these same reasons that Power Games dictators clutch so tightly onto their mute buttons. Even today, over two centuries after the birth of the U.S., almost three billion human beings9 are still deprived of freedom of speech or other core Enlightenment freedoms.

But dictators aren’t the only ones who use mute buttons. Given all of the obvious benefits of free speech, when a culture or a movement or an individual citizen seems threatened by free speech, the first question you should ask is: “Why? What are they so scared of?” Free speech is a tool that helps us see what’s true versus false and right versus wrong—so if you believe truth and virtue are on your side, a vibrant, open discourse is your best friend. And if someone is trying to repress free speech—that tells us something important.

Mute buttons in any form should raise an alarm in all of our heads, though they sometimes seem to go unnoticed. When all you’ve ever known is freedom, it can be easy to forget just how precious it is.

___________

In a world of Power Games, the American forefathers built a different kind of giant—one that didn’t need to be controlled with strings and cudgels because it could think for itself and make its own decisions. A giant human being.

In the late 1700s when the U.S. was born, it was a bit of an oddball on the global scene. But the new country quickly began to thrive. This wasn’t the first time a society replaced an iron cudgel with a constitution—but one had never been done so effectively, on so broad a scale, in modern times. Soon, countries run by constitutions, driven by minds of their own, began springing up all over the world.10.

The founders knew that they didn’t have all the answers. They knew that over time the world would change, the citizens would change, and unpredictable things would happen. They were wise enough to know that no matter how smart they were, their country was a first draft—United States 1.0. The U.S. was a promising child who would need to grow up into a more perfect nation.

So they built a nation that was founded on doubt, not certainty. With a mysterious, foggy future ahead, free speech would give the new nation a way to figure things out as it went: a flashlight to help see the truth, a compass that would help point it towards wisdom, and a mirror that would help an orphan child raise itself.

But when you’re dealing with humans, nothing is easy.

Taking the human out of the Power Games is one thing—taking the Power Games out of the human is quite another. Enlightenment-born constitutions put the Primitive Mind in a cage, but just how strong are those bars?

While the Value Games may be the official way of doing business in the U.S., at the core of every U.S. citizen and government official runs a piece of primitive software that speaks a more ancient language—and in U.S. society, the shadow of a cudgel sometimes seems to loom where it’s not supposed to.

Is the U.S. the Enlightenment come to life? Or is it the Power Games, wearing an Enlightenment disguise?

Probably a little of both.

The U.S. is a story of a nation’s struggle for security, for power, for progress, for wealth. But mostly, it’s a story of a nation’s struggle against itself.

Sounds a little like each of us, doesn’t it?

That’s the thing about building a giant human being. You get the whole package—on a giant scale.

In this post, we got to know how the U.S. works on the surface. But to accomplish our goal in this series—to understand modern societies well enough that we can figure out how to make things better—we’ll need to go deeper. To really understand society, we’ll need to take a closer look at a miniature version of it.

You.

Chapter 7: The Thinking Ladder

___________

To keep up with this series, sign up for the Wait But Why email list and we’ll send you the new posts right when they come out.

Huge thanks to our Patreon supporters for making this series free for everyone. To support Wait But Why, visit our Patreon page.

___________.

Three other places we can hang out:

1) Your odd friendships: 10 types of odd friendships you’re probably a part of

2) All the wealth in the world: What could you buy with $241 trillion?

3) Creepy upsetting children in old ads: Creepy kids in creepy vintage ads

___________.

Sources and related reading:

John Stuart Mill, On Liberty. The old classic.

I cited author and activist Jonathan Rauch a few times in this post. He’s one of the best at articulating why free speech matters. The long quote I included in this post is part of this excerpt from Rauch’s excellent book Kindly Inquisitors.

Economist Max Roser’s incredibly useful site Our World in Data. Specifically, the page on democracy.

It’s an ongoing debate just how much a country like the U.S. is led by the citizen body vs. by politicians vs. by other components like the media. One interesting take that contradicts the idea that the people lead and politicians follow can be found in John Medearis’s book Joseph Schumpeter’s Two Theories of Democracy. He argues that democracy is more a mechanism that fosters competition among leaders, merely held in check by the electoral process.

You can find the ongoing list of sources, influences, and related reading for this series here.

Source link

Author Tim Urban