If the hype surrounding the metaverse results in something real, it could improve the way you live, work, and play. Or it could create a hellworld where you don’t get to be who you are or want to be. Whatever people think they’ve read, the metaverse originally imagined in Snow Crash is not a vision for an ideal future. In the novel, it’s a world that replaced the “real world” so that people would feel less bad about the reality they actually had. In the end, the story is about the destabilization of the individual’s identity and implosion of traditional identities, rather than the securing of a new one.

Even in the real world (a.k.a. meatspace), identity can be hard to pin down. You are who you are, but there are many ways you may define yourself depending on the context. In the latest metaverse discourse there has been lots of talk of virtual avatars putting on NFT-based clothing, skins, weapons, and other collectable assets, and then moving those assets around to different worlds and games without issue. Presentation is just a facet of identity, as the real-world fashion industry well knows.

Learn faster. Dig deeper. See farther.

The latest dreams of web3 include decentralized and self-sovereign identity. But this is just re-hashing years of identity work that focuses on the how (internet standards) and rarely the why (what people need to feel comfortable with identity online). Second Life has been grappling with how people construct a new identity and present their avatars since 2003.

There are many ways that the web today and the metaverse tomorrow will continue to integrate further with our reality:

| Experiences | Examples |

| Online through a laptop like the web today | Posting to Facebook, discussing work on Slack or joining a DAO on Discord. |

| Mobile devices while walking around in the real world | Seeing the comments about a restaurant while standing in front of it, getting directions to a beach or getting access to a private club via an NFT. |

| Mixed and augmented reality (MR/AR) experiences where the digital is overlaid on reality | Chatting with someone who looks like they are sitting next to you or seeing the last message you sent to someone you are talking to. |

| Fully immersive virtual reality (VR) experiences | Going to a chat room in AltspaceVR or playing a game with friends in Beatsaber. |

Before we can figure out what identity means to people in “the metaverse,” we need to talk about what identity is, how we use identity in the metaverse, and how we might create systems that better realize the way people want their identities to work online.

I login therefore I am

When I mention identity, am I starting a philosophical discussion that answers the question “who am I?” Am I trying to figure out my place within an in-person social event? Or do you want to confirm that I meet some standard, such as being over 21?

All of these questions have a meaning in the digital world; most often, those questions are answered by logging in with an email address and password to get into a particular website. Over the last decade, some services like Facebook, Google, and others have started to allow you to use the identity you have with them to log into other websites.

Is the goal of online identity to have one overarching identity that ties everything together? Our identities are constantly renegotiated and unsaid. I don’t believe we can encode all of the information about our identities into a single digital record, even if some groups are trying. Facebook’s real-name policy requires you to use your legal name and makes you collapse all of your possible pseudo-identities into your legal one. If they think you aren’t using a legal name, they require you to upload a government issued document. I’d argue that because people create multiple identities even when faced with account deactivation, it is not their goal to have one single compiled identity.

All of me(s)

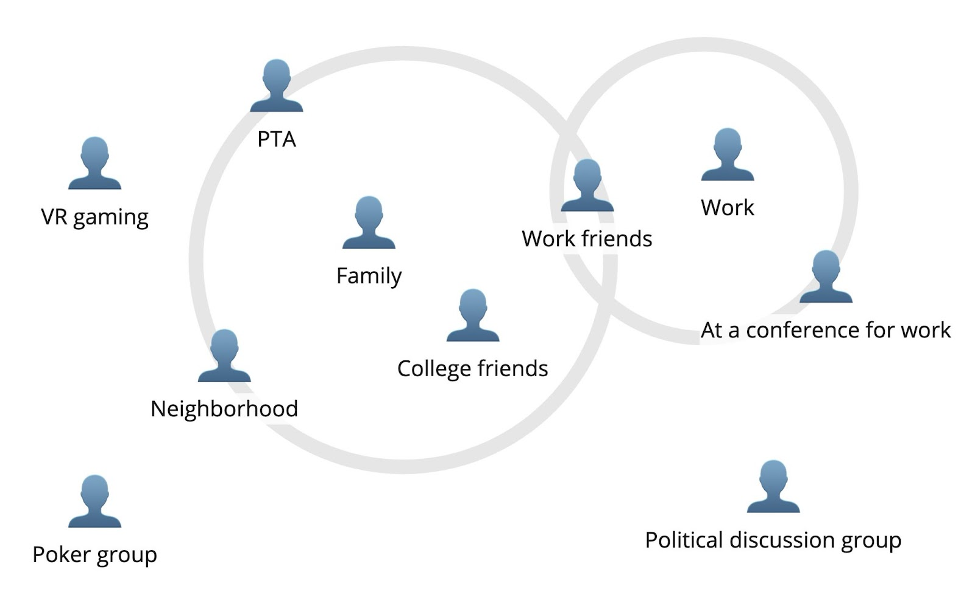

As we consider identities in the metaverse extensions to the identities we have in the real world, we need to understand that we build pseudo-identities for different interactions. My pseudo-identities for a family, work, my neighborhood, PTA, school friends, etc. all overlap to some extent. These are situations, contexts, realms, or worlds that I am part of, and that extend to the web and metaverse.

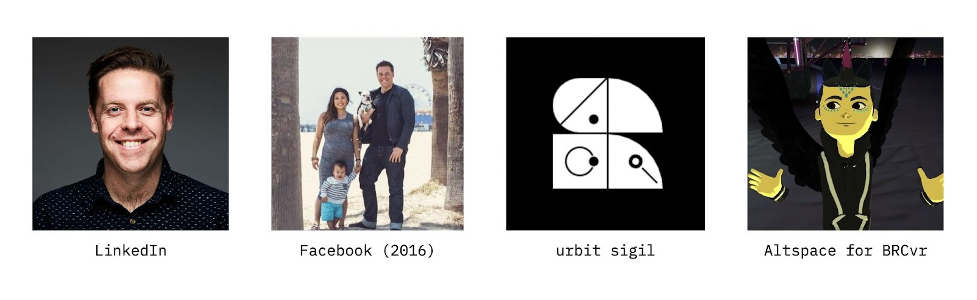

In most pseudo-identities there are shared parts that are the “real me,” like my name or my real likeness. Some may be closer to a “core” pseudo-identity that represents more of what I consider to be me; others may just be smaller facets. Each identity is associated with a different reputation, a different level of trust from the community, and different data (profile pictures, posts, etc.).

The most likely place to find our identities are:

- Lists of email and password pairs stored in our browsers

- Number of groups we are part of on Facebook

- Gamer tags we have on Oculus, Steam, or PSN

- Discords we chat on

- …and the list goes on

Huge numbers of these identities are being created and managed by hand today. On average, a person has 1.75 email addresses and manages 90 online accounts. It will only get more complex and stranger with the addition of the metaverse.

There are times that I don’t want my pseudo-identity’s reputations or information to interact with a particular context; for these cases, I’ll create a pseudo-anonymous identity. There is a lot of prior work on anonymity as a benefit:

- Balaji Srinivasan has discussed the value of an economy based on pseudonymous identities as a way to “air gap” against repercussions of social problems.

- Jeff Kosseff, professor and author, has recently written a book about the benefits of anonymity “The United States of Anonymous.” In a great discussion on the TechDirt podcast he talks about how the ability to question powers is an important aspect of the ability to be anonymous.

- Christopher “moot” Poole, the creator of 4chan, has often talked about the benefits of anonymous online identities including the ability to be more creative without the risk of failure. Given the large amount of harmful abuse that comes out of communities like 4chan, this argument for anonymity is questionable.

If you link one of my pseudo-identities to another pseudo-identity in a way I didn’t expect, it can feel like a violation. I expect to control the flow of information about me (see Helen Nissenbaum’s work on contextual integrity for insight into a beneficial privacy framework). I don’t want my online poker group’s standing to be shown to the PTA, with which I discuss school programs. Teachers who have OnlyFans accounts have been fired when the accounts are discovered. Journalists reporting on cartel activities have been killed. Twitter personalities that use their real names can be doxed by someone who links their Twitter profile to a street address and mobile phone number. This can have horrible consequences.

In the real world, we have many of these pseudo-identities and pseudo-anonymous identities. We even have an expectation of anonymity in groups like Alcoholics Anonymous and private clubs. If we look to Second Life, some people would adopt core pseudo-identities and others pseudo-anonymous identities.

In the online world and, eventually, the metaverse, we will have more control over the use of our identities and pseudo-identities, but possibly less ability to understand how these identities are being handled by each system we are part of. Our identities can already collide in personal devices (for example, my mobile phone) and communal devices (for example, the voice assistant in my kitchen around my family).

How do you recognize someone in the metaverse?

In the real world we recognize people by their face, and identify them by a name in our heads (if you are good at that sort of thing). We may remember the faces of some people we pass on the street, but in a city, we don’t really know most of the people who we are around.

The person you’re communicating with may show up with a real name, a nickname, or even a pseudo-anonymous name. Their picture might be a professional photo, a candid picture, or an anime avatar, or some immersive presentation. All of these identifiers are protected by login, multi-factor authentication, or other mechanisms–yet people are hacked all the time. A site like Facebook tries to give you assurances that you are interacting with the person you think you’re interacting with; this is one justification for their real-name policy. Still, there is a difference between the logical “this is this person because Facebook says so” and the emotional “this feels like the person because my senses say so.” With improvements in immersion and building “social presence” (a theory of “sense of being with another”), we may be tricked more easily into providing better engagement metrics for a social media site. I may even feel that AI-generated faces based on people I know are more trustworthy than actual images of the people themselves.

What if you could give your online avatar your voice, and even make it use idioms you use? This type of personal spoofing may not always be nefarious. You might just want a bot that could handle low value conversations, say with a telemarketer or bill collector.

We can do better than “who can see this post”

To help people grapple with the increased complexity of identity in the metaverse, we need to rethink the way we create, manage, and eventually retire our identities. It goes way beyond just choosing what clothing to wear on a virtual body.

When you start to add technologies that tie everything you do to a public, immutable record, you may find that something you wish could be forgotten is remembered. What should be “on the chain” and how should you decide? Codifying aspects of our reputation is a dream of web3. The creation of digitally legible reputation can cause ephemeral and unsaid aspects of our identities to be stored forever. And an immutable public record of reputation data will no doubt conflict with legislation such as GDPR or CCPA.

The solutions to these problems are neither simple nor available today. To move in the right direction we should consider the following key principles when reconsidering how identities work in the metaverse so that we don’t end up with a dystopia:

- I want to control the flow of information rather than simply mark it as public or private: Contextual Integrity argues that the difference between “public” and “private” information hides the real issue, which is how information flows and where it is used.

- I want to take time to make sure my profile is right: Many development teams worry about adding friction to the signup process; they want to get new users hooked as soon as possible. But it’s also important to make sure that new users get their profile right. It’s not an inherently bad idea to slow down the creation and curation of a profile, especially if it is one the user will be associated with for a long time. Teams that worry about friction have never seen someone spend an hour tweaking their character’s appearance in a video game.

- I want to experiment with new identities rather than commit up front: When someone starts out with a new service, they don’t know how they want to represent themselves. They might want to start with a blank avatar. On the other hand, the metaverse is so visually immersive that people who have been there for a while will have impressive avatars, and new people will stick out.

- I’m in control of the way my profiles interact: When I don’t want profiles not to overlap, there is usually a good reason. Services that assume we want everything to go through the same identity are making a mistake. We should trust that the user is making a good choice.

- I can use language I understand to control my identities: Creating names is creating meanings. If I want to use something simple like “my school friends,” rather than a specific school name, I should be able to do so. That freedom of choice allows the user to supply the name’s meaning, rather than having it imposed from the outside.

- I don’t want shadow profiles created about me: A service violates my expectations of privacy when it links together various identities. Advertising platforms are already doing this through browser fingerprinting. It gets even worse when you start to use biometric and behavioral data, as Kent Bye from the Voices of VR podcast has warned. Unfortunately, users may never have control over these linkages; it may require regulation to correct.

- I should be warned when there are effects I might not understand due to multiple layers interacting: I should get real examples from my context to help me understand these interactions. It is the service developer’s job to help users avoid mistakes.

Social media sites like Facebook have tried to address some of these principles. For example, Facebook’s access controls for posts allow for “public,” “friends,” “friends except…,” “specific friends,” “only me,” and “custom.” These settings are further modified by the Facebook profile privacy control settings. It often (perhaps usually) isn’t clear what is actually happening and why, nor is it clear who will or won’t be able to see a post. This confusion is a recipe for violating social norms and privacy expectations.

Next, how do we allow for interaction? This isn’t as simple as creating circles of friends (an approach that Google+ tried). How do we visualize the various identities we currently have? More user research needs to go into how people would understand these constructions of identity on a web or virtual experience. My hunch is that they need to align some identities together (like family and PTA), and to separate out others (like gamertags). I don’t think requiring users to maintain a large set of access control lists (ACLs) is the right way to control interaction between identities.

The life of my identity

Finally, identities have life cycles. Some exist for a long time once established, like my family, but others may be short lived. I might try out participation in a community, and then find it isn’t for me. There are five key steps in the lifecycle of an identity:

- Create a new identity – this happens when I log into a new service or world. The new identity will need to be aligned with or separated from other identities.

- Share some piece of information with an identity – every meaningful identity is attached to data: common profile photos, purchased clothing, facial characteristics, voices, etc.

- Recover after being compromised – “oops I was hacked” will happen. What do people need to do to clean this up?

- Losing and recovering – if I lose the key to access this identity, is there a way I can get it back?

- Delete or close an identity, for now – people walk away from groups all the time. Usually they will just drift off or ghost; there should be a better way.

All services that plan on operating in the metaverse will need to consider these different stages. If you don’t, you will create systems that fail in ways that expose people to harm.

Allow for the multiplicity of a person in the metaverse

If you don’t think about the requirements of people, their identities, and the lifecycle of new identities, you will build services that don’t match your users’ expectations, in particular, their expectations of privacy.

Identity in the metaverse is more than a costume that you put on. It will consist of all the identities, pseudo-identities, and pseudo-anonymous identities we take on today, but displayed in a way that can fool us. We can’t forget that we are humans experiencing a reality that speaks to the many facets we have inside ourselves.

If all of us don’t take action, a real dystopia will be created that keeps people from being who they really are. As you grow and change, you will be weighed down by who you might have been at one point or who some corporation assumed you were. You can do better by building metaverse systems that embrace the multiple identities people have in real life.

If you lose your identity in your metaverse, you lose yourself for real.